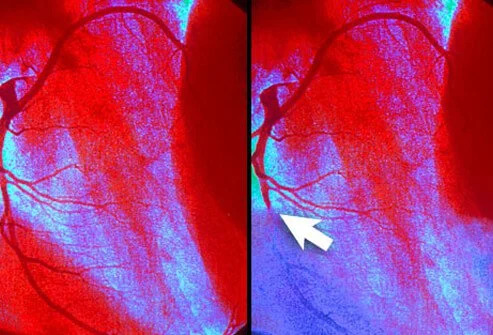

A heart attack, also known as a myocardial infarction, occurs when a portion of the heart muscle is deprived of blood supply.

When does a heart attack happen?

The following are some of the things that can happen to impending heart attack.

These six signs and symptoms of a heart attack are more common in women:

- Pain in the chest. Chest pain is the most common sign of a heart attack, but some women may feel it in a different way than men.

- Arm(s), back, neck, or jaw pain

- Stomach pain

- Shortness of breath

- Nausea

- Chest pain

Four signals to tell if you’re having a “silent heart attack.”

- Pain

- Pressure

- Fullness and discomfort in the chest, neck, or back.

- Pain in other parts of your body.

Sometimes the pain from a heart attack comes quickly and is very bad. This makes it easy to know and get help.

When does a heart attack start?

People’s lives can be saved if you act quickly. There are medicines that can help stop heart attacks and open blocked blood vessels. These medicines can be given quickly after the symptoms start. A catheterization may be needed to open up the blocked blood vessel. The longer you wait for help, the less likely you are to live and the more damage to your heart there is.

People with chest pain or other heart attack symptoms should call 911 right away, so don’t wait. Check your community plan to see if you need to call a different number. While your first thought may be to drive yourself or the person who had a heart attack to the hospital, it’s better to get an ambulance. An EMS worker can start giving the patient medicine while they drive to the hospital. They also know how to save someone if their heart stops.

Who can help?

If you need help with your heart, you can come to the Doral Health & Wellness Cardiology Center for the best help and care. Clinical excellence and a warm and friendly attitude make us the right choice for consultation, reassurance, and treatment, whether you have symptoms like heart pain or high blood pressure or more complex medical needs. We are here for you. Everyone at our clinic is always a part of the decision-making process, and we make sure they are. We don’t do invasive tests and treatments when there are other ways to get the same results. We can use state-of-the-art cardiac imaging that is up to date.

Specialty at Doral Health

In order to figure out what’s wrong with your heart, your Doral cardiologist studies your symptoms, runs tests, and checks you out. Take care of your heart today by making an appointment with a cardiologist at Doral Health & Wellness today.